Mattel, the company behind Barbie and Hot Wheels, entered the video game business in 2006 with the HyperScan, a console for tweens that combined physical trading cards with digital gaming. It was released on October 23, 2006, for $69.99, just as the PlayStation 3 and Nintendo Wii were expected to dominate the holiday season.

Its cube-shaped body, which features a blazing red circular RFID reader, resembles a toy that is unsure whether it wants to be portable or immovable. It wobbles on flat surfaces, a design defect that makes it seem like an afterthought. A permanently attached AV cable comes out of its side, a cost-saving measure that screams cheap. Two controller ports use six-pin mini-DIN connectors, the same as old PC mice, but with a flat edge to prevent you from plugging in non-proprietary devices—though as one reviewer found out a slim mouse plug can sneak past this restriction. The controllers themselves are flimsy, with mushy buttons, a single unresponsive analog stick that pops out of place and four unlabeled shoulder buttons that feel like they were added as an afterthought. A USB port on the back, unused, hints at unrealized potential. Power comes through an unusual 7.5-volt DC connector, another weird choice in a system full of them.

Sale

Mattel Jurassic World Rebirth Bite N Blast Mosasaurus Action Figure & Mini Dilophosaurus, Wide Jaw…

- Jurassic World lives Bring the excitement and thrills of Jurassic World Rebirth home with this distinctive Mosasaurus with exciting Bite ‘N Blast…

- Total attack Kids can easily hold the tail and press the button, or manually open the prey-seeking jaw. The jaw opens wide, ready to ‘Bite’ and…

- Spitting image Hold the tail and press the button again and the Mosasaurus ‘Blasts’ the Dilophosaurus prey back out of its mouth

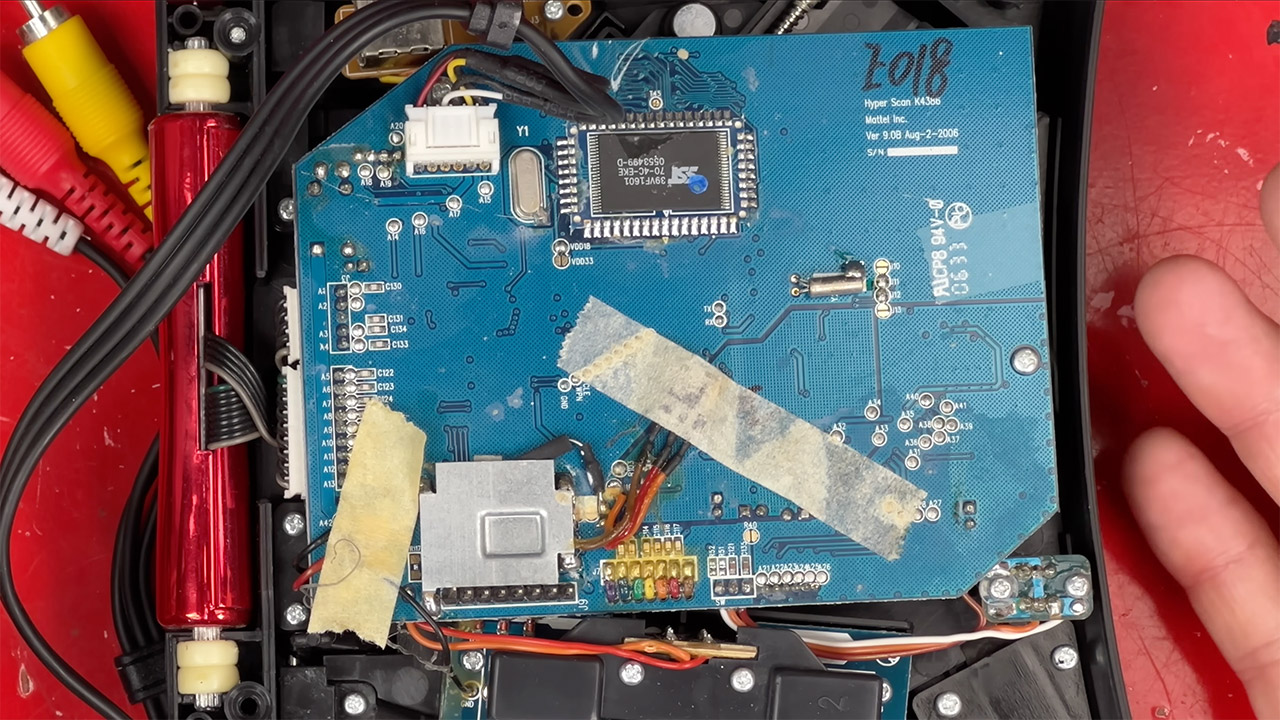

Underneath the HyperScan’s shell is the Sunplus SPG290 system-on-a-chip, a 32-bit processor running at 108 MHz with 16 MB of DDR SDRAM. This is the same chip used in bootleg consoles and plug-and-play devices. It could only produce 2D graphics at 640×480 resolution—adequate for 1996 but laughable by 2006 when competitors were pushing 3D worlds. Games came on CD-ROMs, a choice that felt retrograde as the industry was moving to DVDs. Loading times were interminable, often over a minute, and tested the patience of its young audience. The console’s defining feature was its 13.56 MHz RFID scanner, supplied by Innovision Research and Technology. This scanner read special “IntelliCards” that unlocked characters, abilities and levels in games. Each card was thick with an embedded coil and chip and used RFID to communicate wirelessly with the console, powered by a magnetic field from the scanner. Mattel called this revolutionary, possibly the first use of RFID in a gaming console, but the execution was far from smooth.

The HyperScan’s game library was super thin with only 5 titles: X-Men, Marvel Heroes, Spider-Man, Ben 10, and Interstellar Wrestling League. Two others, Avatar: The Last Airbender and Nick Extreme Sports, were cancelled before release. Each game came with a disc and 6 or 7 cards but to fully experience the game you had to buy booster packs for $10 each which contained randomized cards. For example the X-Men set required 56 cards which would cost $159.99 with the console and game—a steep ask for a tween’s allowance. The X-Men game, a clunky 2D fighter rated T for Teen, came with the console while the others, rated E10+, were side-scrollers or simplistic fighting games. The card system was meant to merge the collectible craze of Pokémon cards with video games and failed. Scanning cards was unreliable, often required multiple attempts and the information they held—stats and abilities—could have been printed on the card itself, rendering the RFID gimmick more frustrating than fun.

Inside a mess of glue, sticky tape and melted plastic holds everything together. A pair of jumpers taped onto the motherboard suggests last minute tweaks, possibly for programming or resetting the system. A countersunk screw meant for wood or metal, not circuit boards, hints at quality control issues. The RFID scanner’s coil is visible on the board but the red LEDs are haphazardly glued in place. A 2MB flash ROM likely stored save data, though it’s unclear if the cards themselves held progress, as one reviewer speculated. The CD-ROM drive, driven by a motor chip, is attached to the motherboard by a delicate ribbon cable making disassembly a pain. Every part of this thing feels like a cost cutting measure from the 16 MB of RAM to the lack of 3D capabilities, Mattel just wanted to get this product out the door without refining it.

Compared to the VTech V.Flash, a similar kid-focused console released a month earlier, the HyperScan felt underpowered and overpriced. PC World later named it one of the worst gaming systems ever, a distinction it shares with other failures. Retailers quickly marked down the price, consoles to $9.99 and games to $1.99 by the end of its run. The two-player value pack, sold online with an extra controller and 12 additional X-Men cards, couldn’t save it. By 2007 Mattel pulled the plug, cancelled all remaining games and cards and left hobbyists to mess around with homebrew demos like a CD-door test and a 3D wireframe experiment.